The landscape of hepatitis C (HCV) management has undergone a near-fundamental transformation over the past couple of years. As new treatment options puff up like popcorn kernels on a hot stove and our understanding of the virus deepens, it's important to revisit what's changed -- and what further changes 2014 may hold in store.

Late in 2013, Andrea Cox, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, presented an update on HCV coinfection for an audience of HIV care providers. Read on for a summary of key points from her talk, including selected slides (which have been reposted with her permission).

The Hard Facts

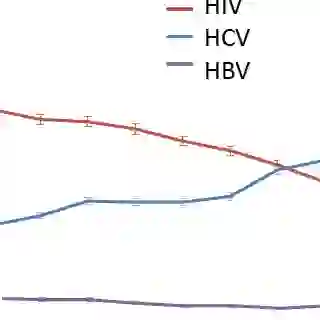

HCV infection kills as many as 15,000 people a year in the U.S. -- and appears to be on the rise, Cox noted. In 2006, HCV surpassed HIV as a cause of mortality in the U.S.

HCV is the leading cause of end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in not only the U.S., but many other countries as well, Cox said. The virus is also the leading cause of non-AIDS-related death among people with HIV -- a fact that becomes less surprising when accounting for the reality that an estimated 25% of the HIV-infected population is also living with HCV.

HIV Accelerates Damage

HIV "essentially drives every part of the bad part of [the] pathway" of HCV's progression in humans, Cox said. Acute infection, chronic infection, cirrhosis and late-stage complications (HCC, transplant and death) are all exacerbated by the presence of HIV.

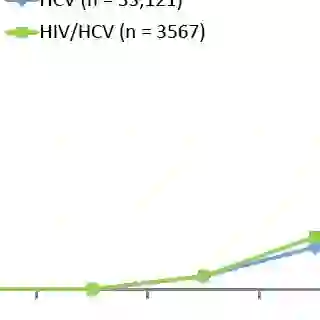

A 2008 study indicated that, over time, HIV-coinfected patients are increasingly more likely than HCV-monoinfected patients to develop cirrhosis.

The Challenges of Traditional Treatment

Although the effect of HIV coinfection on HCV disease progression increases the priority of HCV treatment, traditional HCV therapy -- peginterferon plus ribavirin -- has a notoriously brutal toxicity profile and a depressingly low rate of success in HIV-coinfected people.

"Interferon has an adverse effect on essentially every system in the body," Cox said. "This is particularly important in our HIV-infected individuals, because we tend to see a little bit more depression," as well as other complications including anemia, neutropenia, cytopenia, nausea, cardiovascular events and concurrent infections, she added.

In addition, historically, HIV care providers have found the question of when to refer a patient into HCV care a challenge, due to uncertainties around the timing of (and potential interactions with) HIV therapy and their awareness of HCV treatment's poor efficacy and tolerability, Cox noted.

Difficulties With Monitoring

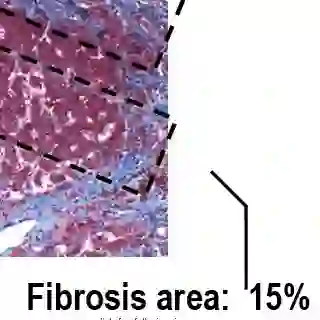

Meanwhile, liver monitoring and HCV disease staging have typically meant conducting a biopsy -- which, though it can be helpful for diagnosis of other forms of liver disease, can inform the need for HCC screening and can effectively predict end-stage liver disease development, is also expensive, invasive and quite painful. "We don't find a lot of patients particularly eager to undergo that."

The validity of a biopsy can also sometimes be a matter of debate, due to the risk that the liver sample taken may -- depending on the cross section of the organ obtained -- misrepresent the total amount of fibrosis. Due to the discomfort involved in the procedure, repeated testing is often less than ideal for many patients.

Meanwhile, other typical forms of non-invasive tests have limited value when it comes to determining HCV disease stage, Cox said. Measuring HCV RNA levels can have important prognostic value; determining HCV genotype is key to informing the type and duration of therapy to use; and CT scans or MRIs can spot evidence of cirrhosis. But none of these methods are effective at staging a patient's disease, Cox said, which has historically been critical for gauging whether treatment should be initiated.

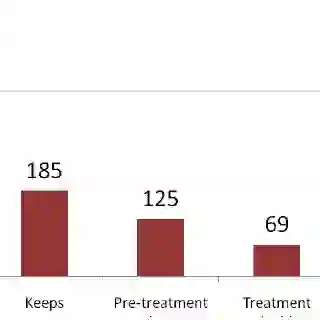

The HCV Treatment Cascade

Between the significant liabilities of traditional therapy and the significant shortfalls of common monitoring techniques, it is perhaps unsurprising that clinical rates of HCV treatment success in HIV-coinfected patients are often miserably low. Cox pointed to a 2006 study of 845 patients receiving regular HIV care via the Johns Hopkins HIV clinic around the turn of the century -- a study that found only 6 of the 845 actually achieved a sustained virologic response on HCV therapy.

What makes these numbers particularly alarming is that they may not even be an extreme example. "Those data come from a clinic where people are more than a little in tune to the need to treat hepatitis C," Cox said. "It's probably worse in other clinics."

Cox added that the challenges of real-world HCV treatment success are not unique to the HIV-coinfected population. "In a VA [U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs] study of about 100,000 patients with hep C, regardless of HIV or not, only about 2 and half percent were cured of their hepatitis C," she said.

Turning the Tide: Staging

Improvements in liver monitoring continue to lag behind. Cox pointed out that a number of less-invasive blood tests -- FibroTest, SHASTA, FIB-4, Forns and APRI, for instance -- have been shown to have some value. "In this very inexpensive test, the AST to platelet ratio index is actually pretty good at predicting liver disease when compared to liver biopsy -- which again, isn't perfect," Cox said.

A newer, more advanced, completely non-invasive method -- transient elastography (a.k.a. FibroScan), approved in the U.S. in 2013 -- appears quite useful for picking up high-level liver disease and relatively useful for spotting lower-level disease, Cox said. However, the test -- which gauges liver stiffness by passing ultrasound waves through the organ -- is less effective the more overweight a patient is, and with an average price tag in the $120,000 range, Cox suggested that the technology remained an option that many facilities were unable to afford.

Turning the Tide: Treatment

The need to effectively stage a patient's liver disease may be lessened in the wake of dramatic improvements on the HCV treatment front. Much as the evolution of HIV antiretrovirals into highly effective, minimally toxic options has rendered the "when to start" question increasingly moot for HIV treatment, multiple new generations of HCV medications may have the same effect on treatment of the virus.

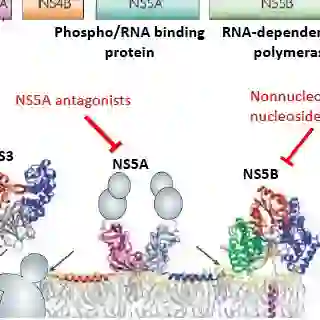

Several waves of direct-acting antiretrovirals are now washing up on the HCV treatment shoreline. As researchers hone in more directly on HCV-specific proteins to disrupt, side effects become less likely and efficacy increases.

"The previous barriers to therapy are really disintegrating at this point in time, so I'm hoping that will encourage all of us to refer, and/or treat ourselves, more and more of these patients," Cox said. "We really don't need biopsy in many cases; the treatments are just much better in terms of efficacy and tolerability now."

Protease Inhibitors Make a First Splash

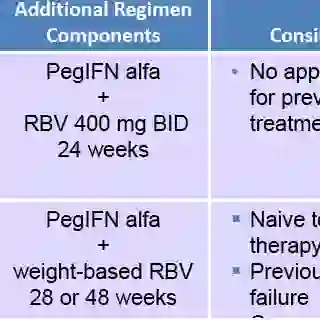

The first wave of new HCV drugs arrived in the form of two protease inhibitors, boceprevir (Victrelis) and telaprevir (Incivek), which were approved in the U.S. in 2011 for the treatment of HCV genotype 1. They have not yet been approved specifically for HIV-coinfected patients, however -- and Cox suggested that their day in the sun may be setting.

In clinical trials, boceprevir and telaprevir have both been shown to dramatically increase HCV treatment success rates in therapy-naive, HIV-coinfected patients. But they still must be taken with interferon, and both drugs have been found to exacerbate the adverse effects seen among patients taking interferon-based therapies. Between those sobering data and extensive drug-interaction concerns with HIV medications, "it's not easy to take these medications," Cox said.

The Second Wave Arrives

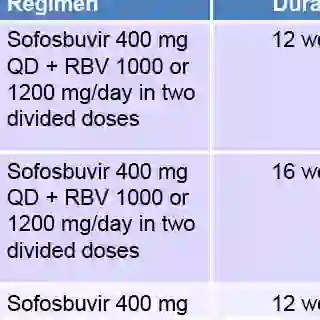

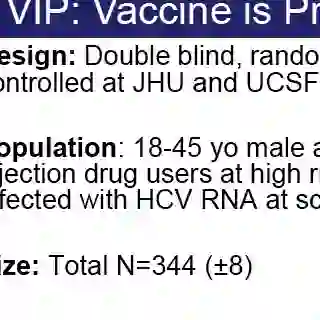

Two more HCV drugs were newly approved in late 2013: the protease inhibitor simeprevir (Olysio) and the nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir (Sovaldi).

By comparison to the two previously approved HCV protease inhibitors, simeprevir appears to be significantly more friendly toward coadministration with HIV medications (particularly HIV protease inhibitors) and has a high efficacy rate in HCV treatment-naive coinfected patients, even allowing many to dramatically shorten the typical course of HCV therapy. However, the drug must still be coadministered with peginterferon, leaving toxicity as a major issue.

Peginterferon is also part of a sofosbuvir-containing regimen at the moment, but only for genotype 1 patients. For patients with genotype 2 or 3, the drug is dosed alongside only ribavirin, and dramatically lower adverse event rates accompany that indication. Sofosbuvir also appears to have virtually no interactions with HIV antiretrovirals.

A New Tide Approaches

Simeprevir and sofosbuvir both represent a further step in the evolution of more effective, less-toxic HCV treatment options. But they, too, are just the beginning. Numerous direct-acting antiretrovirals are currently moving through the latter stage of the development pipeline, suggesting that the treatment landscape by early 2015 may look as different from the present as the present does from just a few years earlier.

For the notoriously hard-to-treat HCV genotype 1 in particular, Cox states: "It's hard to predict, but right now in advanced testing, there are some combinations that are inteferon-sparing" yet have very high sustained virologic response rates -- and may not even require the use of ribavirin.

HCV Vaccine Is Still a Holy Grail

As HCV treatment options continue to improve and we develop better tools to aid our monitoring of patients for liver disease progression, an obvious question comes to mind: Is there still clear value in striving to develop an as-yet elusive preventive vaccine for HCV?

For Cox, the answer is a resounding yes. Even as treatments grow more effective, they also carry huge price tags and are still associated with numerous side effects. Data also indicate that HCV treatment cannot protect a patient against reinfection. And a high hurdle remains to providing effective care to HCV-infected patients who may be in need of treatment, in part because the disease is usually initially asymptomatic, and in part because the highest rates of HCV infection rates tend to occur among deeply marginalized groups (such as injection drug users and those living in resource-poor regions) for whom access to HCV testing and care are often severely limited.

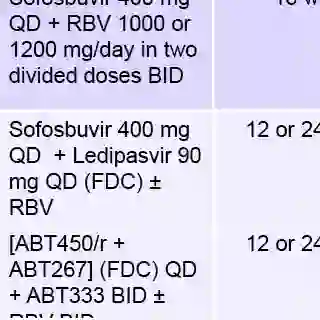

The U.S. health department appears to agree with this assessment, Cox said. In addition to calling a preventive HCV vaccine a "high priority" in its 2011 Viral Hepatitis Action Plan, it has also funded the Vaccine is Prevention study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial that will seek to enroll 344 patients. Cox is one of two principal investigators on the study, alongside Kimberly Page, Ph.D., M.P.H., a professor at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine.

For More Information

As this article has made clear, the HCV treatment landscape is rapidly shifting, and today's realities are quickly giving way to tomorrow's developments. Keep yourself informed by checking in with quality resources for health care providers.

- TheBodyPRO.com's Hepatitis C Spotlight Series

- HCVguidelines.org, jointly developed by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' official HCV prevention/treatment guidelines for HIV-infected adults and adolescents